Learning & Teaching

I have degrees in neuroscience, philosophy, and world heritage, and I have worked in areas of transportation, technology and development. I’m a researcher in the philosophy faculty at Universität Heidelberg, where I’m weaving my work from these fields into a tapestry in the tradition of phenomenology. This work builds a philosophy of mind ‘beyond dichotomy’ and orients ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ as words that assess different forms of our continual movement. This work is built from neuroscience research relative to the hippocampal formation, an area of the brain considered crucial for both memory and navigation and often referred to colloquially as our cognitive SatNav or ‘the brain’s GPS’.

A shorthand for this might be ‘mind as motion as mind’ or an understanding of cognitions as ‘steering activities’ or forms of navigability. I sometimes discuss mind and movement as way-making, so as to understand that these are referring to the same ongoing process, even if we cannot reduce them into one another. Navigabilities are the ways we represent that way-making. All these phrases are shorthand for what I work through in my thesis, and upcoming book, in more detail. To actually understand what I am saying, which is quite radical, is also quite frustrating, for it requires a deep shift in our current bifurcated habits of communication and categorization.

Still, there is also something about it that is easy to notice in everyday life. It is already present in the ways we discuss our ‘train of thought’ or how we might ‘better navigate’ this or that conceptual or emotional space. We also intuitively understand that our technologies are tied to our forms of movement and navigability and that the vehicles and devices we build shift our patterns of thinking, remembering, and feeling. There are rich traditions in many disciplines that have inspired this work. For a partial list of all those inspiring this project, please see here: INSPIRATIONS.

Way-making, Steering, Navigability

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been asking: What are minds, and how do they connect to movement? More recently, that question has take new forms such as: How can we better understand ourselves in the context of our interactions within our environments? What sorts of philosophies guide us as we build our cities and technologies, especially in transportation? How might we enter a new way of thinking that can hold the space for what now seem like dichotomies and contrasts?

I hope to share ways of studying the mind at various levels and across different species using the idea of Navigability—which is a term for coming to awareness of the regularities that create our thoughts and movements, and an awareness that thinking is movement.

What we mean by cognition or mind is steering activity as consciousness. Thinking and remembering and feeling are steering activities as consciousness, as I lay it out via research into the hippocampal formation, which is the part of the brain linked to remembering/knowledge acquisition as well as to spatial navigation.

This steering is done either with or without awareness of its steering activity, and its movement can be assessed in different ways as itself and by itself, and within different landscapes—those we commonly call 'mental' and those we call 'physical' and those we call 'virtual' etc. These assessments cannot be reconciled with one another, even though they are explorations of the same process. This furthers the development of the potentials of steering, which is the further development of consciousness. An absence of steering is a dispersal of concentrated energy and focus—to die, or to dissolve form. To steer does not imply one center, but rather the potential of numerous stances that feel central when taken. We are multiplicities.

This champions many approaches of the past that understand mind as a form of movement, either literally or metaphorically. I mean it literally, though not in the sense of the body moving from A to B, but rather of ‘thinking’ and ‘remembering’ as actions that can be noticed or traced through the regularities of conscious encounter.

Movement is a way of knowing and knowing is a way of moving.

A term I use often to discuss all this movement is way-making. Way-making is a term inspired by Taoism that can be understood as the movement of the body as well as the movement of the mind: “Way-making blunts the sharp edges and untangles the knots; it softens the glare and brings things together on the same track.” (Ames and Hall, 2003). This framing seeks to link the work of many who are rethinking the dualistic views that influence our actions, relationships, and fields of study.

While the ideas of way-making and navigability may seem complex or esoteric at first, they have clear effects on:

how we treat and study mental health

what is meaningful for us and the quality of our experience

our relationship to the environment

the strength of science and spirituality, and why they sometimes appear incompatible

the choices we make about the design of our cities, business, and forms of transportation

how we use and build our technology, and what those technologies mean in our everyday lives

how we create and change our habits and path-dependencies

Holding Paradox

*

Holding Paradox *

Two phrases I use often are holding the paradox and moving beyond dichotomy. These are meant to open the possibility of holding what seems irreconcilable or divided within a shared space. Way-making is the term opening to that space without trying to reconcile how it appears from every position. Opening to Embrace Paradox.

We often define our world and ourselves by contrasting things. This has been useful, but it has also led us to divide ourselves and our worlds into what we see as irreconcilable divisions. In philosophy, the idea of mental and physical, or mind and body, as different substances or properties is an example of this.

This either/or thinking appears everywhere—on social media, for example, where you can choose between thumbs up or down, like or unlike, follow or unfollow. This shows how philosophy connects to technology, and how my work involves developing both.

Across all these fields, however, a fresh perspective is emerging. It focuses on a way of thinking that avoids rigid categories and judgments. Rather than answering questions that assume the same viewpoint, we recognize everyone has different stories and perspectives, so no single answer can satisfy everyone. This increases complexity, but it also offers an expansive understanding of what it means to be aware and alive.

Hippocampus

Though I’ve spent a lot of time in traditional universities, the greatest education for me comes through living and learning from others, and from the rather unorthodox and nomadic lifestyle I’ve lived. My drive for better understanding mind beyond traditional dichotomy comes from my own personal witness of struggles with mental and physical health.

Inspiration for the particular framing of this philosophy came from my studies in neuroscience and specifically from a long line of research relative to an area of the brain known as the hippocampus. This area of the brain is known for two actions that once seemed irreconcilable or contradictory but are now being understood as different paths towards understanding the same process. You can find more here to start, or you can listen to some of my research conversations on this topic at Love and Philosophy, Hippocampus History.

The ways we make in cognitive space

Way-making is a term inspired by Taoism, and can be understood as the movement of the body as well as the movement of the mind: “Way-making blunts the sharp edges and untangles the knots; it softens the glare and brings things together on the same track.” (Ames and Hall, 2003 in Bouton, 2024).

Way-making is the larger term I use at times for this process when it is not modelled. Way-making expresses that beings make their way through all they encounter, all day long, for as long as they are living. This term does not imply division, beginnings or ends. It is thinking at all layers of life, and of all beings—any body in its movement is its own form of intelligence. This might seem a simple start for those of us who are hard-nosed philosophers, but it is actually quite radical and precise: It means any living being that makes its way through any measurable space is intelligent.

Way-making refers to our movements through all these spaces in our lives, and asks we not try and collapse binaries into one another, but let them be and explore the space around them, which in turn opens them as multiplicities.

Unorthodox Paths

Ramblings while trying to accept my trajectory.

Once while discussing the success of my book Thinking Small, a fellow philosopher slipped out the following— Oh Andrea, I’m so surprised it went like that.

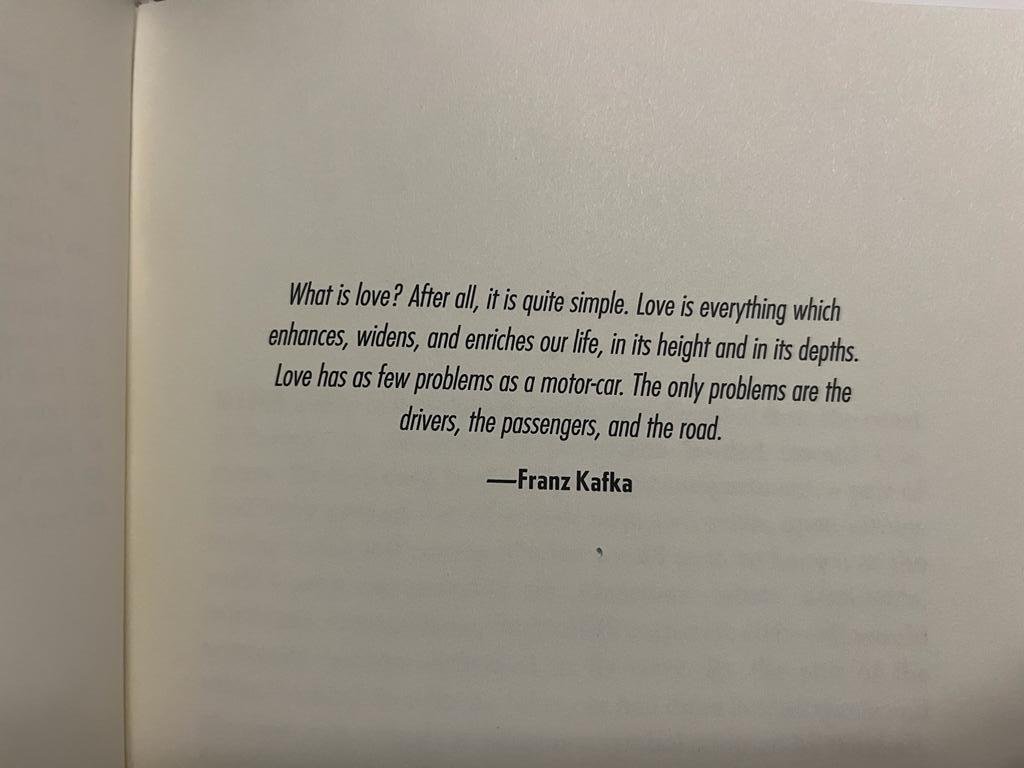

I understood the sentiment. I imagined other friends in our little group were feeling it when they looked at me. I’d set out to write a philosophical text about ecological dialectics and ended up writing a book about history and cars (the long, strange trip of the Volkswagen Beetle). It was hard to see how it all fit, but I had no regrets.

I’d fallen in love with the Bug and its story, unabashedly. To me, the story was a narrative of the idea of holding paradox, and of thinking as movement. Writing that book, and working with the people I collaborated with on it, was a true gift. It was also a path I had not expected to take. After co-creating and sustaining an interdisciplinary journal, I had visions of Camus, de Beauvoir and Arendt. Now I’d been named a cultural historian and automotive journalist— wonderful titles, but ones that caught me off guard.

All those days scribbling out stories while working in independent bookshops in Seattle and NYC; all those nights drinking wine in European cafes while writing, studying, and discussing philosophy—it was hard to see how writing about transportation fit to my life. My friend’s “surprise” was a way of acknowledging my discomfort. Even before the book was published, I’d packed up for Mongolia and signed on to work for the Peace Corps, restless to push further at expectations and find another way of seeing the world.

After the Peace Corps and some years wandering, completing a project for the U.S. Embassy, working for artists and collectors, and continuing as an editor, writer and translator—the connections between all these divergent desires slowly began to become clear. Through all my exploration, a few themes and questions kept recurring:

How do we find our way? And how does our way find us?

In my early university years, I’d written a thesis (Hegel, Rorty, Bohm) towards a dynamical definition of mind. In it, I’d explored mind as an active process. I began to imagine cognition as though it were another form of navigation, a way we move and are moved by the world.

The intimacy of our thoughts and memories can often make it feel as if we are shut off from the relationships and ecologies that sustain and create us. I began to wonder—Is there a way to shift perspective and sense that same mind as ecological? Are there sensory motifs and thought patterns threading through our ecology and linking us with all we encounter? If so, how might our awareness of those paths & patterns lead to healthier communal action & agency?

With those questions in mind, I settled in Berlin to supplement my philosophy degree with a degree in neuroscience. I started studying and working in labs that focused on navigation, computation and cognition, and I continued developing a philosophy around ecological orientation and waymaking, exploring how our sensory relations come together in a common atmosphere.

Exploring the continuity of memory, thinking and action, my forthcoming work is connected by the desire to understand the dynamic spatiotemporal connections between ecology and mind, and to do so beyond traditional dichotomies. Looking back now, I can see that my first book was moving towards something similar—the history of transportation is about new ways of experiencing space and time, both socially and technologically.

The New York Times recently asked the legendary comedian and creator Jerry Seinfeld to name his literary guilty pleasure, and he named my book Thinking Small. This was a great gift, for more reasons than one, as he starts by saying: “I don’t feel guilt to begin with.” The way he turns the question on its head parallels the movement of my own evolution these days as I’ve accepted the strange path of my life, and no longer much care if what I do satisfies niche-based proprieties. This path may not fit expectations of normalcy, but what path does?

My former discomfort about being part of so many seemingly contradictory worlds no longer makes much sense. Rather I understand that the more perspective we can handle, the more the contradictions become compliments. The strange topography of my life is authentic, evidence of my hunger to explore space, to cover as much emotional and mental terrain as possible, to widen into other points of view and experiment with ways of expanding “I” through the “we” of ecology; asking what it means to be here, and how we come to know that we are.

Rethinking technology and ecology.

On a metaphorical level, we have long understood life is a journey, but research relative to navigation and orientation across the biological and cognitive sciences is currently coming together to help us address urgent issues of mental and environmental health. A large part of this change requires a reorientation in our understanding of technology and its relation to mind.

Even more crucial, however, is a reorientation in how we understand the human position and what it means to be part of an ecology. In other words, it requires shifting through an individualistic perspective towards discovering an ecological one.

This is a primary concern of my work and research. Together with my colleagues, I hope to offer and illuminate an ecological orientation, a shift in our stance to self and landscape that helps us better understand what mind is, how it develops, and what this means for the paths we choose as individuals and as a living planet.

My writings and work are focused on this emerging reorientation at the intersection of science and the humanities. I am also developing technology towards deepening our everyday awareness of this connection in ways that will ease our minds and reconnect our sensualities.